Home>North America>Life of AB Gregory

Chapter 9: Novitiate

After the trip to Greece, the young George returned and dedicated himself completely, first to the monastic life, and then to iconography. His visit to Mount Athos was a great inspirational blessing for him. Seeing young men his own age embarking on a life of which he had now embarked on, and also watching someone painting icons for the first time, was of great significance. He had brought to the monastery the book The Ladder of Divine Ascent, which is the bible for monastics, as it were. He read this book with great zeal and endeavored to understand every insertion that St. John of the Ladder made in his book. To say the least, this book inspired him throughout his monastic life. He had also brought to the monastery the book The Rudder of the Holy Orthodox Church, which contained all the canons of the Church, which are Christian commandments for both the lay people and the clergy.

At one time, the monastery was reading excerpts from the life of St. Andrew, the Fool-for-Christ‘s-Sake. This life had a profound effect upon young George. The life of any Fool-for-Christ‘s-Sake is such a contradiction to life as we know it in the world. The life of a Fool-for-Christ‘s-Sake is the life of the Resurrection, the confirmation of the Gospel, the taking of the Kingdom by force, as the Scriptures say. To hear of someone doing this for the first time evokes great admiration and awe for such a holy way of life. Saint Andrew‘s life inspired the young George, so much so that he went up into his cell and fell down on his face and prayed to St. Andrew that he also would be able to emulate the life of a Fool-for-Christ‘s-Sake. Moreover, he understood that the life of a holy fool consists primarily of the life of one slandered, and he pondered on this aspect greatly. How could someone endure to be so slandered, and receive it with gladness, and not respond again in the same manner? These ideals were embedded in the young George, and he took it to heart that if he were slandered throughout the rest of his life, he would trust in God as St. Andrew trusted in God, and not repay evil for evil. Thus he wished to live his monastic life obediently, but if accused falsely, he would not defend himself.

The young George read The Ladder of Divine Ascent with very great care and tried to understand the mentality that is necessary for a man to succeed as a monk. Within the first four chapters the criteria for success in the monastic life became very evident: exile from one‘s home and family, detachment from all worldly cares, the strictest obedience to which one can possibly attain, which is the cutting off of one‘s own will and reasoning, and lastly to accept dishonor as honor, and shame as glory. In fact, it was just like being a Fool-for-Christ‘s-Sake.

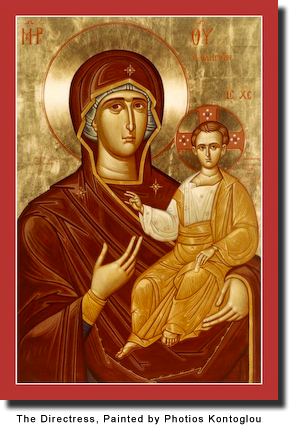

That ideal or standard was very quickly going to be put to the test. George‘s family began to fear that because he had not returned to their home, that perhaps the young man was indeed committed to the monastic life. So his mother came to the monastery by herself. She was weeping and wailing, beseeching and pleading, that she see her son and that he come back into the world. His twin brother was about to be married and leave the home, so she needed the support of her other son. The fact that he was becoming a monastic would add absolutely nothing materially to her support. She spent the whole morning there, creating no small disturbance. Even when the lunch bell rang, she would not stop her groaning. The reception room was right next to the dining room. She would not come to eat with them but wanted to stay in the reception room mourning as do many women in the east, bewailing their grief, and sighing and talking to themselves and calling upon Christ or the Virgin for their help. While the monks were sitting and eating, her cries were loud enough that the monks could not hear the appointed readings for that time during the meal. Somewhat exasperated, the young George got up from the table and came to his mother and besought her, “Please, stop making so much noise because the monks cannot hear the reader.” And in tears she said to him in a loud voice, “But you are my son!” And the young George, in exasperation and without thinking, pointed to the life-size icon of the Virgin Mary, painted by Photios Kontoglou, which was in the reception room, and he pointed to her and said, “Do you see her? She is my mother now!”

When his mother looked up at the Virgin, whose face in this icon had an expression of great joy and comfort, all her tears ceased and all her anguished cries subsided. George walked back to the dining room/trapeza and the meal continued as if she were not there anymore. After the meal, they went to meet her again and she was all calmed down and was somehow comforted, but only God knows how. She never again came to the monastery beseeching that her son leave. She only came on special feast days, especially Pascha, with the rest of the family to greet her son and the rest of the fathers. Indeed, when she was told that her son was going to be tonsured, she was present and expressed her sorrow for her past actions when she had come to the monastery and bewailed his departure.

As is the case with so many who desire to start a new life, expectations are never in accordance with reality. The same can be said with the young George. Starting the monastic life was a great struggle. Although he was young and pure, still the effects of the world on anybody being raised in America have a detrimental effect on one who desires to live the monastic life. In America, one is encouraged to think for himself, to make decisions on his own, to judge all things, to be confident in his own ideas, and even to take pride in himself. All these things are to a certain degree are an obstacle to one who wishes to be a monastic. The young George had left studying electrical engineering in the university. He was directing his life to be a “success” in the world: to get married, have children, own a home, and own a few cars, be in debt to the bank for 30 years … what is jestingly referred to in monastic circles as “the whole catastrophe,” but somehow viewed as a “successful life.”

Now he was confined to one room, studying one mode of life, the monastic life, which embraces prayer, virtue, chastity, obedience, stability, etc., which is also known as “the art of arts and the science of sciences.” Having the example of St. Andrew the Fool-for-Christ‘s-Sake before his eyes and the instruction of The Ladder of Divine Ascent at his side, he was able to progress, but not without difficulty.

The struggle which is most common to all was not absent from the young George, and that was of obedience. It was told him by another novice there at the monastery that he should not accept the obedience of iconographer because his abbot, Fr. Panteleimon, had an obsession about iconography. Father Panteleimon had a tremendous desire to have a gifted person like this as a member of his brotherhood. Indeed George was told that no novice who attempted iconography under Abbot Panteleimon ever succeeded. In fact, they were all driven away from the monastery by the abbot‘s conduct towards young aspirants in this field. The abbot never took up this art on his own, nor ever held a brush, nor mixed colors, nor ever even made a sketch. Notwithstanding this, he would instruct novices in this art and they would be driven to despair because of the lack of success and the abbot‘s intolerance and impatience.

|

Archbishop Gregory Dormition Skete P.O. Box 3177 Buena Vista, CO 81211-3177 USA |

|

|

|

Copyright 2011 - Archbishop Gregory Last Updated: July 12, 2011 |